Articles of interest

10th August 2022

Book in Focus

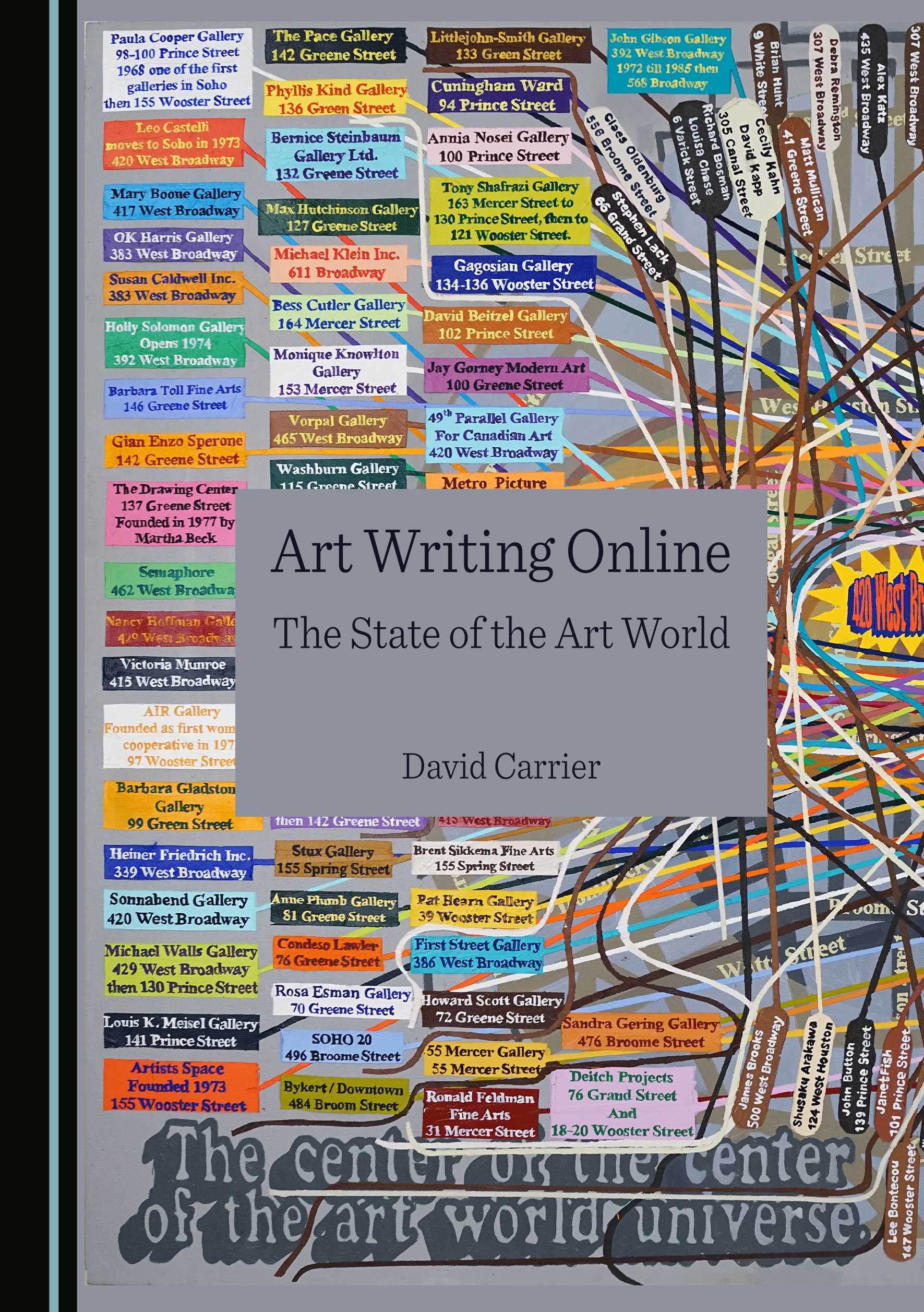

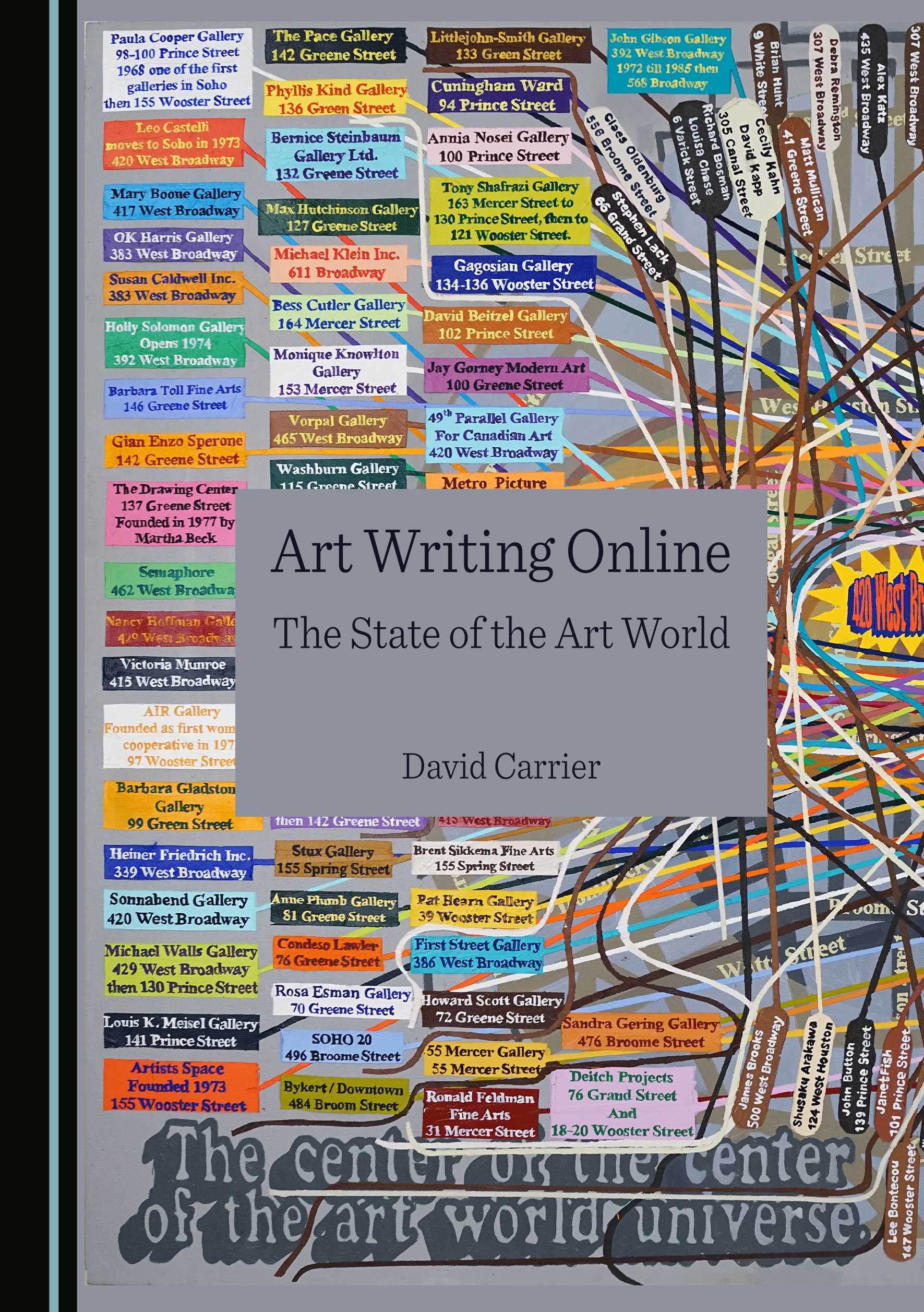

Art Writing Online

The State of the Art World

By David Carrier

Starting Out in the Art World: Fragments from a 1980s Memoir

When I published Art Writing Online: The State of the Art World, I found myself looking back, and thinking about how I started out as an art critic. Sometimes you can better understand where you are going by looking backwards historically in this way. Then perhaps younger art writers, who face a very different situation, will find such a personal account of interest.

To become a professional philosopher, you go to graduate school and get a PhD. Then if you want to rebel, you can do that after you have tenure. Yet, how do you become an art critic? That’s more complicated, for art critics are self-taught and there is no licensing system. In the late 1970s, when I was teaching philosophy, I found in Artforum writing very unlike any that I had studied, a series of visionary essays by Joseph Masheck, which offered a highly original theory of abstract painting. When I contacted him, he urged that I write criticism too, and introduced me to an artist, Sharon Gold. Then I entered a parallel universe, a place very unlike the academic world. The first time that I was paid for my art writing, thinking that someone had made a mistake, I hastened to cash the check. Philosophers are not paid to write.

A major transition was taking place in the New York art world. Clement Greenberg’s formalism had worn out its welcome; Leo Steinberg, his apparent successor, was not publishing criticism; and Greenberg’s rebellious followers, Michael Fried and Rosalind Krauss were well established. Furthermore, alternatives were in play: Robert Pincus-Witten’s post-formalist writing; Thomas McEvilley’s deployment of Indian Philosophy; and some others. At this period, our present concerns with race had not yet been developed much, and the role of women in the art world was only beginning to be properly discussed. However, to speak of this moment as defined by the search for a critical method is misleading. Some important art, photorealism for example, did not seek theorizing. Also, many critics, who were poets, such as Bill Berkson, denied that critics needed a method. In a revealing 1982 exhibition, ‘critical perspectives’ at Alanna Heiss’s P. S. 1, a number of leading critics, including Masheck, were each assigned a room, and asked to curate a statement. Academic aesthetics did not provide much preparation for understanding this situation. I learned, however, from artists, most especially Thomas Nozkowski and Sean Scully, and from Garner Tullis, the printer who commissioned my book about his monotypes.

As an untenured philosopher, I knew how to proceed. Two major philosophers, Nelson Goodman and Richard Wollheim, published treatises on aesthetics in 1968. Therefore, my early academic publications discussed their work. Nevertheless, the art world wasn’t interested in them, as I learned when my long essay on Goodman published in Artforum didn’t attract any response. To become a critic, you needed to see art and find a satisfying way of writing. In the galleries, there was plenty to see and having an artist to guide you is very helpful. I was lucky, I often made the rounds with David Reed. At Jaap Rietman, the artist’s bookstore in Soho, you could find the books likely to be influential.

When I had (too many) drinks with Greenberg, thinking like a philosopher, I tried to reconstruct his claims. ‘So, I contradict myself’, he said: ‘so what?’ If he didn’t have a method, maybe I didn’t need one either. Looking back, what’s most surprising is that those who pursued this search for a critical method turned to Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, and Jacques Lacan. Not generally taken seriously by the important American philosophy departments, these French writers were very influential in the art world. An earlier generation of New York painters were influenced by Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s essay “Cézanne’s Doubt,” which was translated in 1964. Compared with the post-structuralist texts, that was a straightforward commentary. Derrida, Foucault and Lacan didn’t focus on visual art and if you hadn’t studied Edmund Husserl and Jean-Paul Sartre, it was almost impossible to comprehend this French writing. To understand Krauss’s influential essay “Sculpture in the Expanded Field” (1979), you needed to realize that her Greimas square, borrowed from the literary critic Fredric Jameson, came from an obscure semiotician Algirdas J. Greimas, October. The journal she co-founded employed Mandarin prose to champion politically critical art. The Octoberists liked to say that their journal titles alluded to Eisenstein’s 1928 film, not the Bolshevik revolution. Although, of course that film was about the 1917 revolution. Many people felt highly ambivalent, at best, about October. Its taste was narrow, and like the Surrealists, it expelled deviant theorists. When I was naive enough to submit an intellectual biography of Krauss to MIT press, which is the October publisher, I got a ferocious rejection. The editor could not imagine that I both deeply admired her and found some of her claims totally implausible. The kind of argumentation that philosophers are accustomed to was simply alien to this editor. Oddly enough, however, when I published the book elsewhere, she told me that she liked it.

I hope that someone will write a full history of October. I believe that this journal succeeded in the 1980s because it satisfied a real felt need. Just as Alois Riegl, Aby Warburg and Erwin Panofsky had developed a method for art history in the early twentieth century; so, it seemed that art criticism too needed a method, one adapted to graduate school teaching. What was behind these changes were harsh economic realities. As difficult as academic life had become, by comparison, the traditional important role of the independent scholar was simply impossible. No other group of critics developed so influential a worldview as October. Nonetheless, the curators and dealers proceeded mostly on their own. Kirk Varnedoe, chief curator of painting and sculpture at MoMA, who was never associated with that journal, surely had much more influence. Some of the artists October championed became famous, but so did many others too. In any event, just as the October Revolution turned bad by the late 1920s, so the status of October changed. Part of the problem was the contradictions inherent in the original October project of politically critical art. To the extent that this art was successful in the marketplace, how could anyone seriously maintain that it remained critical? When Barbara Kruger has museum shows and sells branded merchandise, then obviously she’s got a significant role in the system she critiques. Justifiably so, because her work is visually brilliant and when in a recent review in this journal, I spoke of Richard Serra’s new sculpture as “the ultimate billionaire’s art,” I alluded to this obvious contradiction. How can sculpture which is so expensive to make really be critical of its support system as often as his early work was said to do?

What, however, has most dramatically revealed the limitations of October is the recent expansion of the art world, to focus on Black artists (from everywhere) and to include all forms of contemporary work from every visual culture. Without venturing into the commercial galleries, you need only walk through the most recent rehang of MoMA to see this. Who can theorize all of this art? Certainly not the senior writers at October, though David Joselet has sketched a promising plan. Academic philosophers typically debate without much immediate reference to politics. By contrast, art world discussion often is highly political. “David Carrier is a hack for US capitalist ideology”: that not-unusual published response to my Hyperallergic review of a Jerusalem show of Soviet art captures the tone of much discussion. State socialism may be dead, but the Fourth International still lives! Philosophical debate is pure, for the issues are, as we say, academic. Although, because art critics are evaluating commodities, unavoidably, whatever their personal politics, they work within a capitalist system. Therefore, my sense is that often they have a guilty conscience. At openings, the art world social system brings together two usually disparate groups, collectors and critics. I have read enough of Henry James to be fascinated by these situations. What’s important, however, is to succumb neither to despair nor envy.

For reasons that Barry Schwabsky has outlined in the introduction to The Perpetual Guest, while art writers have a marginal, almost non-existent place in the art market, still their discourse plays an often-essential role in establishing the meanings of contemporary art. “The meaning of an artwork is made and remade by anyone prepared to formulate a contribution to the creative act already embodied in it.” Nevertheless, this is another story, and so spelling it out is the task for another occasion. For all of the changes the art world has undergone, I’ve retained the desire that inspired me in the 1980s to see as much as possible, especially in the smaller spaces and, so if this account is history, some of it relatively ancient, the issues remain of passionate interest. The search for a critical method remains a live issue.

My reviews in Art Writing Online show how dramatically the art world has changed. A number of the journals I wrote for, Arts Magazine (edited by Schwabsky), Art International and Tema Celeste have ceased publication. There is great energy in on-line publications, Brooklyn Rail and Hyperallergic. The new prominence of women and Black artists is an amazing change, giving reason to be optimistic. In this radically new situation, the theorizing that engaged me in the 1980s has ceased to be of commanding importance. In my recent writing, I have been concerned to devote attention to art from every visual culture, writing in an intuitive way that I hope is genuinely accessible. You need only set any review from this new publication against any of my 1980s publications to see this dramatic development. Right now, the art world is changing drastically and quickly, in ways that are sure to challenge future historians.

Notes:

A selection of my 1980s criticism appears in my The Aesthete in the City: The Philosophy and Practice of American Abstract Painting in the 1980s (1994).

My Garner Tullis. The Life of Collaboration (1998) is available on Ebay.

Barry Schwabsky, The Perpetual Guest. Art in the Unfinished Present (London: Verso, 2016).

David Carrier taught philosophy in Pittsburgh and art history in Cleveland and China. He has been a Lecturer at Princeton University, a Getty Scholar, a Clark Fellow, and a Senior Fellow at the National Humanities Center, USA. He has lectured extensively in China, Europe, New Zealand, and the United States, and has published books on art criticism and art history; Nicolas Poussin; Charles Baudelaire’s art criticism; the comic strip; Rosalind Krauss; Sean Scully; the art museum; world art history; Proust and Warhol; the art gallery; art from outside the art world; and the contemporary artists Maria Bussmann, Lawrence Carroll and Warren Rohrer. In addition, he has published art criticism in many journals, including Artforum, ArtsMagazine, the Burlington Magazine, and Tema Celeste. Recently he has written extensively for the Brooklyn Rail and Hyperallergic.

Art Writing Online: The State of the Art World is available now in Hardback at a 25% discount. Enter code PROMO25 at checkout to redeem.